Embodied Knowing vs. Rational Calculation

Embodied Knowing vs. Rational Calculation

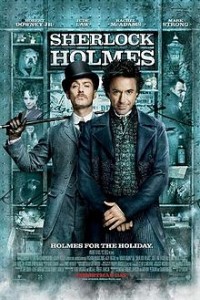

Tonight I saw the latest Sherlock Holmes movie starring Robert Downey Jr. as Holmes and Jude Law as the good Dr. Watson. When the sequel, “A Game of Shadows” was announced, I was reminded of an early fight scene in the 2009 movie (“Sherlock Holmes”) also featuring Downey and Law. The portrayal of the fight raises interesting questions about how we know what we know.

Of course Sherlock Holmes is supposed to be a genius and able to see everything in detail. He is the master of both memory, immediate perception and future prediction of his own actions and those of others. The kind of detailed in-depth knowing that is portrayed in the fight scene from the movie is by every measure impossible. I discussed some of the difficulties of memory, perception and imagination in my last post.

You can watch a video here. (Warning: it is a fight scene and includes violent interaction between Holmes and another man accompanied by a jeering crowd.)

This week I’ve been working on two papers. Both are about embodied knowing and wise judgement. In the light of my study I am fascinated by the portrayal of the Holmes fight scene. Here are some things it makes me wonder about . . .

In the scene, Holmes slows down the action and we overhear a rationally calculated process for each tactic and strategy he will use to take the other man down. My first question is: could this even be accurate or possible? Whether the answer is yes or no to this question, it is still fun and interesting to explore. . . .

Holmes plans each moves, and then executes them flawlessly. He is the quintessential “Cartesian man.” So of course portraying him this way is part of the mystique and charm that is Sherlock Holmes.

In the ring Holmes and his unnamed opponent spar and punch for a few minutes. Then in the midst of the fight Holmes’ love-interest Irene Adler, played by Rachel McAdams, shows up. She leaves her handkerchief as a calling card for him to see draped over the fight ring. He looks for her around the ring, and while looking, he gets an unexpected bump on the back of the head from his opponent and is thrown to the ground.

Upon recovering enough to stand, Holmes spots Adler, who winks and distracts him further with some unintelligible activity. However, Holmes rationally overcomes his feelings for Adler, and plans a take-down of the big opponent he’s fighting. He narrates his plan inside his own head (which we see in slow-motion w/step-by-step narrative descriptions). Then he carries out the plan flawlessly.

Holmes uses rational even forensic knowledge – of body and mind – to plan his defeat.This raises yet another question: When turned loose in an actual situation would it have worked as he imagined (or fantasized)?

Portraying the scene in this way obfuscates the ways that situated knowing of a boxer might work in a non-dramatized ‘real’ fight (without producer, director, scores of staff and actors). Thus another question arises: How does practice – consistent rehearsal of performance, accompanied by knowledge and honed skill – prepare a boxer for a moment like the movie fight scene?

And further questions are on my mind as well: How might the situation itself give rise to knowing what to do in the moment? How do factors like language, embodiment, memory, situated skills, and relationality give shape and framework to the movie scene as well as everyday fist fights?

I prefer not to support violence, but movies are a kind of fantasy about violence that we can’t ourselves engage in without major consequences (which may be why violent movies are so satisfying for some viewers). Both recent Sherlock Holmes movies are entertaining as well as raising interesting questions about human intelligence, skill development, rational calculation and embodied knowing in a lived situation.

So go see the movie(s)! And if you do, let’s talk.